Hawaiian sovereignty movement

| Part of a series on the |

| Hawaiian sovereignty movement |

|---|

|

| Main issues |

| Governments |

| Historical conflicts |

| Modern events |

| Parties and organizations |

| Documents and ideas |

| Books |

The Hawaiian sovereignty movement (Hawaiian: ke ea Hawaiʻi) is a grassroots political and cultural campaign to reestablish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom of Hawaii out of a desire for sovereignty, self-determination, and self-governance.[2][3]

Some groups also advocate some form of redress from the United States for its 1893 overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani, and for what is described as a prolonged military occupation beginning with the 1898 annexation. The movement generally views both the overthrow and annexation as illegal.[4][5]

Palmyra Atoll and Sikaiana were annexed by the Kingdom in the 1860s, and the movement regards them as under illegal occupation along with the Hawaiian Islands.[6][7]

The Apology Resolution the United States Congress passed in 1993 acknowledged that the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom was an illegal act.[8]

Sovereignty advocates have attributed problems plaguing native communities including homelessness, poverty, economic marginalization, and the erosion of native traditions to the lack of native governance and political self-determination.[9][10]

The forced depopulation of Kaho'olawe and its subsequent bombing, the construction of the Mauna Kea Observatories, and the Red Hill water crisis caused by the US Navy's mismanagement are some of the contemporary matters relevant to the sovereignty movement.

It has pursued its agenda through educational initiatives and legislative actions. Along with protests throughout the islands, at the capital (Honolulu) itself and other locations sacred to Hawaiian culture, sovereignty activists have challenged U.S. forces and law.[11]

History

[edit]Coinciding with other 1960s and 1970s indigenous activist movements, the Hawaiian sovereignty movement was spearheaded by Native Hawaiian activist organizations and individuals who were critical of issues affecting modern Hawaii, including the islands' urbanization and commercial development, corruption in the Hawaiian Homelands program, and appropriation of native burial grounds and other sacred spaces.[12] In the 1980s, the movement gained cultural and political traction and native resistance grew in response to urbanization and native disenfranchisement. Local and federal legislation provided some protection for native communities but did little to quell expanding commercial development.[10]

In 1993, a joint congressional resolution apologized for the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy, and said that the overthrow was illegal.[12][8] In 2000, the Akaka Bill was proposed, which provided a process for federal recognition of Native Hawaiians, and gave ethnic Hawaiians some control over land and natural resource negotiations. But sovereignty groups opposed the bill because of its provisions that legitimized illegal land transfers, and it was criticized by a 2006 U.S. Commission on Civil Rights report (which was later reversed in 2018)[13] for the effect it would have on non-ethnic Hawaiian populations.[14] A 2005 Grassroot Institute poll found that most Hawaiian residents opposed the Akaka Bill.[15]

Background

[edit]Native Hawaiians' ancestors may have arrived in the Hawaiian Islands around 350 CE, from other areas of Polynesia.[16] By the time Captain Cook arrived, Hawaii had a well-established culture, with a population estimated between 400,000 and 900,000.[16] Starting in 1795 and completed by 1810, Kamehameha I conquered the entire archipelago and formed the unified Kingdom of Hawaii. In the first 100 years of contact with Western civilization, due to disease and war, the Hawaiian population dropped by 90%, to only 53,900 in 1876.[16] American missionaries arrived in 1820 and assumed great power and influence.[16] Despite formal recognition of the Kingdom of Hawaii by the United States[17] and other world powers, the kingdom was overthrown beginning January 17, 1893, with a coup d'état orchestrated mostly by Americans within the kingdom's legislature, supported by armed sailors landed by the USS Boston.[16][18]

The Blount Report is the popular name given to the part of the 1893 United States House of Representatives Foreign Relations Committee Report about the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii. U.S. Commissioner James H. Blount, appointed by President Grover Cleveland to investigate the events surrounding the January 1893 coup, conducted the report. It provides the first evidence that officially identifies U.S. complicity in the overthrow of the government of the Kingdom of Hawaii.[19] Blount concluded that U.S. Minister to Hawaii John L. Stevens had carried out unauthorized partisan activities, including the landing of U.S. Marines under a false or exaggerated pretext to support anti-royalist conspirators; the report also found that these actions were instrumental to the revolution's success and that the revolution was carried out against the wishes of a majority of the population of the Hawaiian Kingdom and/or its royalty.[20]

On December 14, 1893, Albert Willis arrived unannounced in Honolulu aboard the USRC Corwin, bringing with him an anticipation of an American invasion in order to restore the monarchy, which became known as the Black Week. Willis was Blount's successor as United States Minister to Hawaii. With the hysteria of a military assault, he staged a mock invasion with the USS Adams and USS Philadelphia, directing their guns toward the capital. He also ordered Rear Admiral John Irwin to organize a landing operation using troops on the two American ships, which were joined by the Japanese Naniwa and the British HMS Champion. On January 11, 1894, Willis revealed the invasion to be a hoax.[21][22] After the arrival of the Corwin, the provisional government and citizens of Hawaii were ready to rush to arms if necessary, but it was widely believed that Willis's threat of force was a bluff.[23][24]

On December 16, the British Minister to Hawaii was given permission to land marines from HMS Champion for the protection of British interests; the ship's captain predicted that the U.S. military would restore the Queen and Sovereign ruler (Lili'uokalani).[23][24] In a November 1893 meeting with Willis, Lili'uokalani said she wanted the revolutionaries punished and their property confiscated, despite Willis's desire for her to grant them amnesty.[25] In a December 19, 1893, meeting with the leaders of the provisional government, Willis presented a letter by Liliuokalani in which she agreed to grant the revolutionaries amnesty if she were restored as queen. During the conference, Willis told the provisional government to surrender to Liliuokalani and allow Hawaii to return to its previous condition, but the leader of the provisional government, President Sanford Dole, refused, claiming that he was not subject to the authority of the United States.[24][26][27]

The Blount Report was followed in 1894 by the Morgan Report, which contradicted Blount's report by concluding that all participants except for Queen Lili'uokalani were "not guilty".[28]: 648 On January 10, 1894, U.S. Secretary of State Walter Q. Gresham announced that the settlement of the situation in Hawaii would be up to Congress, following Willis's unsatisfactory progress. Cleveland said that Willis had carried out the letter of his directions rather than their spirit.[23] Domestic response to Willis's and Cleveland's efforts was largely negative. The New York Herald wrote, "If Minister Willis has not already been ordered to quit meddling in Hawaiian affairs and mind his own business, no time should be lost in giving him emphatic instructions to that effect." The New York World wrote: "Is it not high time to stop the business of interference with the domestic affairs of foreign nations? Hawaii is 2000 miles from our nearest coast. Let it alone." The New York Sun said: "Mr. Cleveland lacks ... the first essential qualification of a referee or arbitrator." The New York Tribune called Willis's trip a "forlorn and humiliating failure to carry out Mr. Cleveland's outrageous project." The New York Recorder wrote, "The idea of sending out a minister accredited to the President of a new republic, having him present his credentials to that President and address him as 'Great and Good Friend,' and then deliberately set to work to organize a conspiracy to overthrow his Government and re-establish the authority of the deposed Queen, is repugnant to every man who holds American honor and justice in any sort of respect." The New York Times was one of the few New York newspapers to defend Cleveland's decisions, writing, "Mr. Willis discharged his duty as he understood it."[23]

After the overthrow, the Provisional Government of Hawaii became the Republic of Hawaii in 1894, and in 1898 the U.S. annexed the Republic of Hawaii in the Newlands Resolution, making it the Territory of Hawaii.[29][30] The territory was then given a territorial government in an Organic Act in 1900. While there was much opposition to the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii and many attempts to restore it, Hawaii became a U.S. territory in 1898 without any input from Native Hawaiians.[16] It became a U.S. state on March 18, 1959, following a referendum in which at least 93% of voters approved of statehood. By then, most voters were not Native Hawaiian. The 1959 referendum did not have an option for independence from the United States. After Hawaii's admission as a state, the United Nations removed Hawaii from its list of non-self-governing territories (a list of territories subject to the decolonization process).[31]

The U.S. constitution recognizes Native American tribes as domestic, dependent nations with inherent rights of self-determination through the U.S. government as a trust responsibility, which was extended to include Eskimos, Aleuts and Native Alaskans with the passing of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. Through enactment of 183 federal laws over 90 years, the U.S. has entered into an implicit—rather than explicit—trust relationship that does not formally recognize a sovereign people with the right of self-determination. Without an explicit law, Native Hawaiians may not be eligible for entitlements, funds and benefits afforded to other U.S. indigenous peoples.[32] Native Hawaiians are recognized by the U.S. government through legislation with a unique status.[16] Proposals have been made to treat Native Hawaiians as a tribe similar to Native Americans; opponents to the tribal approach argue that it is not a legitimate path to nationhood.[33]

Historical groups

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2016) |

Royal Order of Kamehameha I

[edit]

The Royal Order of Kamehameha I is a Knightly Order established by His Majesty, Kamehameha V (Lot Kapuaiwa Kalanikapuapaikalaninui Ali'iolani Kalanimakua) in 1865, to promote and defend the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi's sovereignty. Established by the 1864 Constitution, the Order of Kamehameha I is the first order of its kind in Hawaii. After Lot Kapuāiwa took the throne as King Kamehameha V, he established, by special decree,[34] the Order of Kamehameha I on April 11, 1865, named to honor his grandfather Kamehameha I, founder of the Kingdom of Hawaii and the House of Kamehameha. Its purpose is to promote and defend the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Until the reign of Kalakaua, this was the only Order instituted.[35]

The Royal Order of Kamehameha I continues its work in observance and preservation of some native Hawaiian rituals and customs established by the leaders of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. It is often consulted by the U.S. government, the state of Hawaiʻi, and Hawaiʻi's county governments in native Hawaiian-sensitive rites performed at state functions.[36]

Hui Kālai'āina

[edit]This organization existed before the overthrow to support a new constitution and was based in Honolulu.[37]

Hui Aloha 'Āina

[edit]

A highly organized group formed in 1883 from the various islands with a name that reflected Hawaiian cultural beliefs.[37]

Liberal Patriotic Association

[edit]The Liberal Patriotic Association was a rebel group formed by Robert William Wilcox to overturn the Bayonet Constitution. The faction was financed by Chinese businessmen who lost rights under the 1887 Constitution. The movement initiated what became known as the Wilcox Rebellion of 1889, ending in failure with seven dead and 70 captured.[citation needed]

Home Rule Party of Hawaii

[edit]After Hawaii's annexation, Wilcox formed the Home Rule Party of Hawaii on June 6, 1900. The party was generally more radical than the Democratic Party of Hawaii. It dominated the Territorial Legislature between 1900 and 1902. But due to its radical and extreme philosophy of Hawaiian nationalism, infighting was prominent. This, in addition to its refusal to work with other parties, meant that it was unable to pass any legislation. After the 1902 election it steadily declined until disbanding in 1912.[citation needed]

Democratic Party of Hawaii

[edit]On April 30, 1900, John H. Wilson, John S. McGrew, Charles J. McCarthy, David Kawānanakoa, and Delbert Metzger established the Democratic Party of Hawaii. The party was generally more pragmatic than the Home Rule Party, and gained sponsorship from the American Democratic Party. It attempted to bring representation to Native Hawaiians in the territorial government and effectively lobbied to set aside 200,000 acres (810 km2) under the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act of 1920 for Hawaiians.[citation needed]

Sovereignty and cultural rights organizations

[edit]ALOHA

[edit]The Aboriginal Lands of Hawaiian Ancestry (ALOHA) and the Principality of Aloha[38] were organized sometime in the late 1960s or 1970s when Native Alaskan and American Indian activism was beginning. Native Hawaiians began organizing groups based on their own national interests such as ceded lands, free education, reparations payments, free housing, reform of the Hawaiian Homelands Act and development within the islands.[39] According to Budnick,[40] Louisa Rice established the group in 1969. Charles Kauluwehi Maxwell claims that it was organized in 1972.[41]

ALOHA sought reparations for Native Hawaiians by hiring a former U.S. representative to write a bill that, while not ratified, did spawn a congressional study. The study was allowed only six months and was accused of relying on biased information from a historian hired by the territorial government that overthrew the kingdom as well as from U.S. Navy historians. The commission assigned to the study recommended against reparations.[42]: 61

Ka Lāhui

[edit]Ka Lāhui Hawaiʻi was formed in 1987 as a local grassroots initiative for Hawaiian sovereignty. Mililani Trask was its first leader.[43] Trask was elected the first kia'aina (governor) of Ka Lahui.[44] The organization has a constitution, elected offices and representatives for each island.[45] The group supports federal recognition, independence from the United States,[46]: 38 and inclusion of Native Hawaiians in federal Indian policy.[42]: 62 It is considered the largest sovereignty movement group, reporting a membership of 21,000 in 1997. One of its goals is to reclaim ceded lands. In 1993, the group led 10,000 people on a march to the Iolani Palace on the 100th anniversary of the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani.[47]

Ka Lāhui and many sovereignty groups oppose the Native Hawaiian Government Reorganization Act of 2009 (known as the "Akaka Bill") proposed by Senator Daniel Akaka, which begins the process of federal recognition of a Native Hawaiian government, with which the U.S. State Department would have government-to-government relations.[48] The group believes that there are problems with the process and version of the bill.[49] Still, Trask supported the original Akaka Bill and was a member of a group that crafted it.[50] Trask has been critical of the bill's 20-year limitation on all claims against the U.S., saying: "We would not be able to address the illegal overthrow, address the breach of trust issues" and "We're looking at a terrible history.... That history needs to be remedied."[51] The organization was a part of UNPO from 1993 through 2012.[52]

Ka Pākaukau

[edit]Ka Pākaukau leader Kekuni Blaisdell[48] is a medical doctor and founding chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of Hawai'i John Burns School of Medicine who advocates for Hawaiian independence.[53] The group began in the late 1980s as the Pā Kaukau coalition with the aim to supply information that could support the sovereignty and independence movement.[54]

Blaisdell and the 12 groups that comprise the Ka Pākaukau believe in a "nation-within-a-nation" concept as a start to independence and are willing to negotiate with the President of the United States as "representatives of our nation as co-equals".[55]

In 1993, Blaisdell convened Ka Ho'okolokolonui Kanaka Maoli, the "People's International Tribunal", which brought indigenous leaders from around the world to Hawaii to put the U.S. government on trial for the theft of Hawaii's sovereignty and other related violations of international law. The tribunal found the U.S. guilty, and published its findings in a lengthy document filed with the U.N. Committees on Human Rights and Indigenous Affairs.[56]

Nation of Hawaiʻi

[edit]The Nation of Hawaiʻi is the oldest Hawaiian independence organization.[57] Dennis Puʻuhonua "Bumpy" Kanahele[58][self-published source?] is the group's spokesperson and head of state.[59] In contrast to other independence organizations that lean to the restoration of the monarchy, it advocates a republican government.

In 1989, the group occupied the area surrounding the Makapuʻu lighthouse on Oʻahu. In 1993, its members occupied Kaupo Beach, near Makapuʻu. Kanahele was a primary leader of the occupation. He is a descendant of Kamehameha I, 7 generations removed.[60] The group ceased its occupation in exchange for the return of ceded lands in the adjacent community of Waimānalo, where it established a village, cultural center, and puʻuhonua (place of refuge).[60]

Kanahele made headlines again in 1995 when his group gave sanctuary to Nathan Brown, a Native Hawaiian activist who had refused to pay federal taxes in protest against the U.S. presence in Hawaii. Kanahele was arrested, convicted, and sentenced to eight months in federal prison, along with a probation period in which he was barred from the puʻuhonua and participation in his sovereignty efforts.[58]

In 2015, Kanahele portrayed himself in the movie Aloha filmed on location in Hawaii at Puʻuhonua o Waimanalo.[61] This was followed by a 2017 episode of Hawaii Five-0 titled "Ka Laina Ma Ke One (Line in the Sand)".[62]

Mauna Kea Anaina Hou

[edit]Kealoha Pisciotta is a former systems specialist for the joint British-Dutch-Canadian telescope[63][64] who became concerned that a stone family shrine she had built for her grandmother and family was removed and found at a dump.[64] She is one of several people who sued to stop the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope[65] and is the director of Mauna Kea Anaina Hou.[66] Mauna Kea Anaina Hou ("People who pray for the mountain",[67][self-published source?]) and its sister group, Mauna Kea Hui, are indigenous Native Hawaiian cultural groups with environmental concerns in Hawaii. The group is described as a "Native Hawaiian organization comprised of cultural and lineal descendants, and traditional, spiritual and religious practitioners of the sacred traditions of Mauna Kea."

The issue of cultural rights on the mountain was the focus of the documentary Mauna Kea—Temple Under Siege, which aired on PBS in 2006 and featured Pisciotta.[64] The Hawaii State Constitution guarantees Native Hawaiians' religious and cultural rights.[68] Many of Hawaii's laws can be traced to Kingdom of Hawaii law. Hawaiʻi Revised Statute § 1-1 codifies Hawaiian custom and gives deference to native traditions.[69] In the early 1970s, managers of Mauna Kea did not seem to pay much attention to Native Hawaiians' complaints about the mountain's sacredness. Mauna Kea Anaina Hou, the Royal Order of Kamehameha I, and the Sierra Club united in opposition to the Keck's proposal to add six outrigger telescopes.[70]

Poka Laenui

[edit]Hayden Burgess, an attorney who goes by the Hawaiian name Poka Laenui, heads the Institute for the Advancement of Hawaiian Affairs.[71] Laenui argues that because of the four international treaties with the U.S. government (1826, 1849, 1875, and 1883), the "U.S. armed invasion and overthrow" of the Hawaiian monarchy, a "friendly government", was illegal in both American and international jurisprudence.[72]

Protect Kahoolawe Ohana (PKO)

[edit]

In 1976, Walter Ritte and the group Protect Kahoolawe Ohana (PKO) filed suit in U.S. federal court to stop the Navy's use of Kahoolawe for bombardment training, to require compliance with a number of new environmental laws, and to ensure protection of cultural resources on the island. In 1977, the U.S. District Court for the District of Hawaii allowed the Navy's use of this island to continue, but directed the Navy to prepare an environmental impact statement and complete an inventory of historic sites on the island.

The effort to regain Kahoʻolawe from the U.S. Navy inspired new political awareness and activism in the Hawaiian community.[73] Charles Maxwell and other community leaders began to plan a coordinated effort to land on the island, which was still under Navy control. The effort for the "first landing" began in Waikapu (Maui) on January 5, 1976. Over 50 people from across the Hawaiian islands, including a range of cultural leaders, gathered on Maui with the goal of "invading" Kahoolawe on January 6, 1976. The date was selected because of its association with the U.S. bicentennial.

As the larger group headed toward the island, it was intercepted by military crafts. "The Kahoʻolawe Nine" continued and landed on the island. They were Ritte, Emmett Aluli, George Helm, Gail Kawaipuna Prejean, Stephen K. Morse, Kimo Aluli, Aunty Ellen Miles, Ian Lind, and Karla Villalba of the Puyallup/Muckleshoot tribe (Washington State).[74] The effort to retake Kahoʻolawe eventually claimed the lives of Helm and Kimo Mitchell. Helm and Mitchell (who were accompanied by Billy Mitchell, no relation) ran into severe weather and were unable to reach Kahoʻolawe. Despite extensive rescue and recovery efforts, they were never recovered. Ritte became a leader in the Hawaiian community, coordinating community efforts including for water rights, opposition to land development, and the protection of marine animals[75] and ocean resources.[75] He now leads the effort to create state legislation requiring the labeling of genetically modified organisms in Hawaiʻi.[76]

Hawaiian Kingdom

[edit]David Keanu Sai and Kamana Beamer are two Hawaiian scholars whose works use international law to argue for the rights of a Hawaiian Kingdom existing today and call for an end to U.S. occupation of the islands.[46]: 394 Trained as a U.S. military officer, Sai uses the title of chairman of the Acting Council of Regency of the Hawaiian Kingdom organization.[77] He has done extensive historical research, especially on the treaties between Hawaii and other nations, and on military occupation and the laws of war. Sai teaches Hawaiian studies at Windward Community College.[78]

Sai claimed to represent the Hawaiian Kingdom in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, a case brought before the World Court's Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague in 2000.[79][80] Although Sai and Lance Paul Larsen agreed to the arbitration, with Larsen suing Sai for not protecting his rights as a Hawaiian Kingdom subject, his actual goal was to have U.S. rule in Hawaii declared a breach of mutual treaty obligations and international law. The case's arbiters affirmed that there was no dispute they could decide, because the U.S. was not a party to the arbitration. As stated in the award from the arbitration panel, "in the absence of the United States of America, the Tribunal can neither decide that Hawaii is not part of the USA, nor proceed on the assumption that it is not. To take either course would be to disregard a principle which goes to heart of the arbitral function in international law."[81]

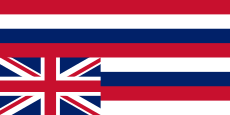

In a 2000 arbitration hearing before the Permanent Court of Arbitration, the Hawaiian flag was raised at the same height at and alongside other countries.[82] But the court accepts arbitration from private entities, and a hearing before it does not mean international recognition.[83]

Hawaiian Kingdom Government

[edit]About 70 members of one separatist group, the "Hawaiian Kingdom Government", which claimed about 1,000 members in 2008, chained the gates and blocked the entrance to ʻIolani Palace for about two hours, disrupting tours on April 30, 2008.[84] The incident ended without violence or arrests.[85] Led by Mahealani Kahau, who has taken the title of queen, and Jessica Wright, who has taken the title of princess, it has been meeting daily to conduct "government business" and demand sovereignty for Hawaii and restoration of the monarchy. It negotiated rights to be on the lawn of the grounds during regular hours normally open to the public by applying for a public-assembly permit. Kahau said that "protest" and "sovereignty group" mischaracterize the group, but that it is a seat of government.[86]

Hawaiian sovereignty activists and advocates

[edit]

- Owana Salazar, claimant to the throne of Hawaiʻi and member of the House of Laʻanui

- Abigail Kinoiki Kekaulike Kawānanakoa was a member of the House of Kawānanakoa.

- Francis Boyle, professor of international law, University of Illinois College of Law and Consultant on Independence, Hawaiian Sovereignty Advisory Commission, State of Hawaii (1993)[87]

- George Helm, musician, and Kimo Mitchell, both d. 1977

- Israel Kamakawiwoʻole, musician; d. 1997

- Bumpy Kanahele, Hawaiian nationalist leader, militant activist, and head of the Nation of Hawaiʻi

- Kahoʻokahi Kanuha, activist and "protector" of Mauna Kea in opposition to the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope. Kanuha defended himself after arrests in the native Hawaiian language or ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi. He chanted his genealogy going back to Umi-a-Liloa and his protection of the mountain and was found not guilty on January 16, 2016.[88]

- Joshua Lanakila Mangauil, Hawaiian cultural practitioner and leader of the international movement to protect Mauna Kea.[89]

- Kawaipuna Prejean (d. 1992), Hawaiian nationalist, activist, advocate for the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, and founder of the Hawaiian Coalition of Native Claims, now known as the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation[90]

- Noenoe K. Silva, political scientist, University of Hawaii at Manoa[91]

- Haunani-Kay Trask, founder of Hawaiian studies, department chair at University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, sovereignty activist, and poet[92]

- Mililani Trask

- Sudden Rush, Hawaiian rap/hip hop (na mele paleoleo) musical group[93]

- Kauka Lukini, Russian revolutionary who became the president of the Senate of Hawaii

Reaction

[edit]In 1993, the State of Hawaiʻi adopted Act 359 "to acknowledge and recognize the unique status the native Hawaiian people bear to the State of Hawaii and to the United States and to facilitate the efforts of native Hawaiians to be governed by an indigenous sovereign nation of their own choosing." The act created the Hawaiian Sovereignty Advisory Committee to provide guidance with "(1) Conducting special elections related to this Act; (2) Apportioning voting districts; (3) Establishing the eligibility of convention delegates; (4) Conducting educational activities for Hawaiian voters, a voter registration drive, and research activities in preparation for the convention; (5) Establishing the size and composition of the convention delegation; and (6) Establishing the dates for the special election. Act 200 amended Act 359 establishing the Hawaiʻi Sovereignty Elections Council".[94]

Those involved with the Advisory Committee forums believed that the question of the political status for Native Hawaiians has become difficult. But in 2000, a panel of the committee stated that Native Hawaiians have maintained a unique community. Federal and state programs have been designated to improve Native Hawaiians' conditions, including health, education, employment and training, children's services, conservation programs, fish and wildlife protection, agricultural programs, and native language immersion programs.[94] Congress created the Hawaiian Homes Commission (HHC) in 1921. The Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) was the result of a 1978 amendment to the Hawaiʻi State Constitution and controls over $1 billion from the Ceded Lands Trust, spending millions to address Native Hawaiians' needs. Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation Executive Director Mahealani Kamauʻu has said that only in the last 25 years have Native Hawaiians "had a modicum of political empowerment and been able to exercise direct responsibility for their own affairs, that progress has been made in so many areas". These programs have opposition and critics who believe they are ineffective and badly managed.[94]

The Apology Bill and the Akaka Bill

[edit]Native Hawaiians' growing frustration over Hawaiian homelands and the 100th anniversary of the overthrow pushed the Hawaiian sovereignty movement to the forefront of politics in Hawaii. In 1993, President Bill Clinton signed United States Public Law 103-150, known as the "Apology Bill", for U.S. involvement in the 1893 overthrow. The bill makes a commitment to reconciliation.[16][95]

U.S. census information shows approximately 401,162 Native Hawaiians living in the U.S. in 2000. Sixty percent live in the continental U.S. and forty percent in Hawaii.[16] Between 1990 and 2000, people identifying as Native Hawaiian had grown by 90,000, while those identifying as pure Hawaiian had declined to under 10,000.[16]

In 2009, Senator Daniel Akaka sponsored The Native Hawaiian Government Reorganization Act of 2009 (S1011/HR2314), a bill to create the legal framework to establish a Hawaiian government. President Barack Obama supported the bill.[96] The bill is considered a reconciliation process, but it has not had that effect, instead being the subject of much controversy and political fighting in many arenas. American opponents argue that Congress is disregarding U.S. citizens for special interests and sovereignty activists believe this will further erode their rights, as the 1921 blood quantum rule of the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act did.[97] In 2011, a governor-appointed committee began to gather and verify Native Hawaiians' names for the purpose of voting on a Native Hawaiian nation.[98]

In June 2014, the US Department of the Interior announced plans to hold hearings to establish the possibility of federal recognition of Native Hawaiians as an Indian tribe.[99][100]

Opposition

[edit]There has also been opposition to the concept of ancestry-based sovereignty, which critics maintain is tantamount to racial exclusion.[101] In 1996, in Rice v. Cayetano, one Big Island rancher sued to win the right to vote in OHA elections, asserting that every Hawaiian citizen regardless of racial background should be able to vote for state offices, and that limiting the vote to Native Hawaiians is racist. In 2000, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in his favor, and OHA elections are now open to all registered voters. In its decision, the court wrote: "the ancestral inquiry mandated by the State is forbidden by the Fifteenth Amendment for the further reason that the use of racial classifications is corruptive of the whole legal order democratic elections seek to preserve....Distinctions between citizens solely because of their ancestry are by their very nature odious to a free people whose institutions are founded upon the doctrine of equality".[102]

Proposed United States federal recognition of Native Hawaiians

[edit]The year of hearings found most speakers with strong opposition to the U.S. government's involvement in Hawaiian sovereignty,[103] with opponents arguing that tribal recognition of Native Hawaiians is not a legitimate path to Hawaiian nationhood and that the U.S. government should not be involved in reestablishing Hawaiian sovereignty.[33]

On September 29, 2015, the United States Department of the Interior announced a procedure to recognize a Native Hawaiian government.[103][104] The Native Hawaiian Roll Commission was created to find and register Native Hawaiians.[105] The nine-member commission has prepared a roll of registered individuals of Hawaiian heritage.[106]

The nonprofit organization Naʻi Aupuni will organize the constitutional convention and election of delegates using the roll, which began collecting names in 2011. Grassroot Institute of Hawaii CEO Kelii Akina filed suit to see the names on the roll, won, and found serious flaws. The Native Hawaiian Roll Commission has since purged the list of names of deceased persons as well as those whose mailing or email addresses could not be verified.

Akina again filed suit to stop the election because funding of the project comes from a grant from the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and because of a Supreme Court decision prohibiting states from conducting race-based elections.[107] In October 2015, a federal judge declined to stop the process. The case was appealed with a formal emergency request to stop the voting until the appeal was heard; the request was denied.[108] On November 24, the emergency request was made again to Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy.[109] On November 27, Kennedy stopped the election tallying and naming of delegates. The decision did not stop the voting itself, and a spokesman for the Naʻi Aupuni continued to encourage those eligible to vote before the November 30, 2015, deadline.[110]

The election was expected to cost about $150,000, and voting was carried out by Elections America, a firm based in Washington, D.C. The constitutional convention has an estimated cost of $2.6 million.[107]

See also

[edit]- Aloha ʻĀina

- Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- Hawaiian home land

- Hawaiian Kingdom-United States relations

- History of Hawaii

- KKCR

- Legal status of Hawaii

- Nation-building

- Opposition to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom

- Puerto Rican independence movement

- Republic of Texas (group)

- Right to exist

- Self-determination

- State formation

- Treaty of Manila

- Tribal sovereignty

- United States involvement in regime change

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights

References

[edit]- ^ Spencer, Thomas P. (1895). Kaua Kuloko 1895. Honolulu: Papapai Mahu Press Publishing Company. OCLC 19662315.

- ^ Michael Kioni Dudley; Keoni Kealoha Agard (January 1993). A call for Hawaiian sovereignty. Nā Kāne O Ka Malo Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-878751-09-6.

- ^ "Kanahele group pushes plan for sovereign nation". hawaii-nation.org. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ "The Rape of Paradise: The Second Century Hawai'ians Grope Toward Sovereignty As The U.S. President Apologizes" Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Perceptions Magazine, March/April 1996, p. 18–25

- ^ Grass, Michael (August 12, 2014). "As Feds Hold Hearings, Native Hawaiians Press Sovereignty Claims". Government Executive. Government Executive. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Purchase of Palmyra Hits Impasse". Pacific Islands Report. February 10, 2000. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Trask, Haunani-Kay (April 2, 2010). "The Struggle For Hawaiian Sovereignty – Introduction". Cultural Survival. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ a b "Public Law 103-150" (PDF). gpo.gov. November 23, 1993. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 7, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ "Historic election could return sovereignty to Native Hawaiians". Archived from the original on October 7, 2016. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Trask, Haunani-Kay (April 2, 2010). "The Struggle For Hawaiian Sovereignty – Introduction". Cultural Survival. Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ Podgers, James (June 1997). "Greetings from independent Hawaii". ABA Journal. American Bar Association. pp. 75–76. ISSN 0747-0088. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ a b Parker, Linda S. "Alaska, Hawaii, and Agreements." Treaties with American Indians: An Encyclopedia of Rights, Conflicts, and Sovereignty, edited by Donald L. Fixico, vol. 1, ABC-CLIO, 2008, pp. 195–208. Gale Virtual Reference Library

- ^ "Civil Rights Panel Backs Federal Recognition For Native Hawaiians". Honolulu Civil Beat. December 20, 2018. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- ^ Beary, Brian. "Hawaiians (United States)." Separatist Movements: A Global Reference, CQ Press, 2011, pp. 96–99.

- ^ "Recent Survey of Hawaii residents shows two out of three oppose Akaka bill". new.grassrootinstitute.org. Honolulu, HI: Grassroot Institute. July 5, 2015. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ponterotto, Casas, Suzuki, Alexander, Joseph G., J. Manuel, Lisa A., Charlene M. (August 24, 2009). Handbook of Multicultural Counseling. SAGE Publications. pp. 269–271. ISBN 978-1-4833-1713-7. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Hawai'i-United States Treaty of 1826" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 18, 2009.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (May 20, 2009). Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars, The: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-85109-952-8. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ Ball, Milner S. "Symposium: Native American Law," Georgia Law Review 28 (1979): 303

- ^ Tate, Merze. (1965). The United States and the Hawaiian Kingdom: A Political History. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 235.

- ^ Report Committee Foreign Relations, United States Senate, Accompanying Testimony, Executive Documents transmitted Congress January 1, 1893, March 10, 1891, p 2144

- ^ History of later years of the Hawaiian Monarchy and the revolution of 1893 By William De Witt Alexander, p 103

- ^ a b c d "Hawaiian Papers". Manufacturers and Farmers Journal. Vol. 75, no. 4. January 11, 1894. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 23, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Willis Has Acted". The Morning Herald. United Press. January 12, 1894. Archived from the original on November 23, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ "Minister Willis's Mission" (PDF). The New York Times. January 14, 1894.

- ^ "Defied By Dole". Clinton Morning Age. Vol. 11, no. 66. January 10, 1894. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 23, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ "Quiet at Honolulu". Manufacturers and Farmers Journal. Vol. 75, no. 4. January 11, 1894. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 23, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1967) [1938], "Chap. 21 Revolution", Hawaiian Kingdom, vol. 3, 1874–1893, The Kalakaua dynasty, Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-87022-433-1, OCLC 47011614, 53979611, 186322026, archived from the original on January 20, 2015, retrieved September 29, 2012

- ^ "Sanford Ballard Dole". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ "Newlands Resolution – Annexation of Hawaii". law.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ "Is Hawaii Really a State of the Union?". Hawaii-nation.org. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ Davianna McGregor (2007). Na Kua'ina: Living Hawaiian Culture. University of Hawaii Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-8248-2946-9. Archived from the original on May 20, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Altemus-Williams, Imani (December 7, 2015). "Towards Hawaiian Independence: Native Americans warn Native Hawaiians of the dangers of Federal Recognition". Intercontinentalcry.org. Archived from the original on July 3, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ Kamehameha V (King of the Hawaiian Islands) (1865). Decree to Establish the Royal Order of Kamehameha I. by Authority. Archived from the original on July 1, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ Ralph S. Kuykendall (January 1, 1967). The Hawaiian Kingdom: 1874–1893, the Kalakaua dynasty. University of Hawaii Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-87022-433-1. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ Bill Mossman (September 6, 2009). "Way of the Warrior: Native Hawaiian lecture series reveals ancient secrets". U.S. Army Garrison-Hawaii. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Neil Thomas Proto (2009). The Rights of My People: Liliuokalani's Enduring Battle with the United States, 1893–1917. Algora Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-87586-721-2. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ "The Principality of Aloha". Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- ^ Fixico, Donald L. (December 12, 2007). Treaties with American Indians: An Encyclopedia of Rights, Conflicts, and Sovereignty [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-57607-881-5. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ Budnick, Rich (January 1, 2005). Hawaii's Forgotten History: 1900–1999: The Good...The Bad...The Embarrassing. Aloha Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-944081-04-4.

- ^ Kahu Charles Kauluwehi Maxwell Sr. "Spiritual connection of Queen Liliuokalani's book "Hawaii's Story" to the forming of the Aboriginal Lands of Hawaiian Ancestry (ALOHA) to get reparations from the United States Of America for the Illegal Overthrow of 1893". Archived from the original on October 17, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Keri E. Iyall Smith (May 7, 2007). The State and Indigenous Movements. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-86179-7. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ Trask, Haunani-Kay (January 1, 1999). From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawaiʻi. University of Hawaii Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8248-2059-6. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ Apgar, Sally (September 25, 2005). "Women of Hawaii; Hawaiian women chart their own path to power". Honolulu Star Bulletin. Archived from the original on August 8, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ Franklin Ng (June 23, 2014). Asian American Family Life and Community. Routledge. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-136-80123-5. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻopua; Ikaika Hussey; Erin Kahunawaikaʻala Kahunawaikaʻala Wright (August 27, 2014). A Nation Rising: Hawaiian Movements for Life, Land, and Sovereignty. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-7655-2. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ Sonia P. Juvik; James O. Juvik; Thomas R. Paradise (January 1, 1998). Atlas of Hawai_i. University of Hawaii Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-8248-2125-8. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Elvira Pulitano (May 24, 2012). Indigenous Rights in the Age of the UN Declaration. Cambridge University Press. p. 323. ISBN 978-1-107-02244-7. Archived from the original on May 14, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ "Akaka bill and Ka Lahui Hawaii position explained". Ka Lahui Hawaii. Archived from the original on January 3, 2015. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ Donnelly, Christine (October 1, 2001). "Akaka bill proponents prepare to wait for passage amid weightier concerns; But others say the bill is flawed and should be fixed before a full congressional vote". Honolulu Star Bulletin. Archived from the original on December 24, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ Bernardo, Rosemarie. "Hawaiians find fault". 2004 Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu Star Bulletin. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ "UNPO: Kalahui Hawaii". unpo.org. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ Chen MS (1994). "Richard Kekuni Blaisdell, M.D., Founding Chair, Department of Medicine, University of Hawai'i John Burns School of Medicine and Premier Native Hawaiian (Kanaka Maoli) health scholar". Asian Am Pac Isl J Health. 2 (3): 171–180. PMID 11567270.

- ^ Ibrahim G. Aoudé (January 1999). The Ethnic Studies Story: Politics and Social Movements in Hawai'i : Essays in Honor of Marion Kelly. University of Hawaii Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8248-2244-6. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ Reinhold, Robert (November 8, 1992). "A Century After Queen's Overthrow, Talk of Sovereignty Shakes Hawaii – NYTimes.com". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ "The Tribunal". Na Maka o ka 'Aina. August 5, 2012. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ John H. Chambers (2009). Hawaii. Interlink Books. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-56656-615-5. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Phillip B. J. Reid (June 2013). Three Sisters Ponds: My Journey from Street Cop to FBI Special Agent- from Baltimore to Lockerbie and Beyond. AuthorHouse. pp. 178–179. ISBN 978-1-4817-5460-6. OCLC 1151416533 – via Internet Archive.[self-published source]

- ^ "United States' Compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights" (PDF). International Indian Treaty Council and the United Confederation of Taino People. p. 4 (note 6). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 2, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ a b "Rebuilding a Hawaiian Kingdom". Los Angeles Times. July 21, 2005. Archived from the original on January 2, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ Chinen, Nate. "Waimanalo Blues: The political and cultural pitfalls into which Cameron Crowe's Aloha tumbles go far beyond poor Allison Ng". Slate.com. Archived from the original on June 1, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ "Hawaii Five-0: Ka Laina Ma Ke One". IMDb. Archived from the original on January 23, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ Castro, Joseph (January 18, 2011). "Bridging science and culture with the Thirty Meter Telescope". Science Line. NYU Journalism. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ^ a b c Tsai, Michael (July 9, 2006). "Cultures clash atop Mauna Kea". The Honolulu Advertiser. The Honolulu Advertiser.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ^ Worth, Katie (February 20, 2015). "World's Largest Telescope Faces Opposition from Native Hawaiian Protesters". Scientific American. Archived from the original on April 21, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ^ Huliau: Time of Change. Kuleana ʻOiwi Press. January 1, 2004. ISBN 978-0-9668220-3-8. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ Patrick Kenji Takahashi (February 29, 2008). Simple Solutions for Humanity. AuthorHouse. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-1-4678-3517-6. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2016.[self-published source]

- ^ Steven C. Tauber (August 27, 2015). Navigating the Jungle: Law, Politics, and the Animal Advocacy Movement. Routledge. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-317-38171-6. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ Sproat, D. Kapuaʻala (December 2008). "Avoiding Trouble in Paradise". Business Law Today. 18 (2): 29. Archived from the original on December 23, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ^ Miller, Steve (2010). "Mauna Kea and the work of the Imiloa Center" (PDF). EPSC Abstracts. 5 (EPSC2010). European Planetary Science Congress 2010: 193. Bibcode:2010epsc.conf..193M. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ Elizabeth Helen Essary (2008). Latent Destinies: Separatism and the State in Hawaiʻi, Alaska, and Puerto Rico. Duke University. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-549-96012-6.

- ^ Laenui, Poka. "Processes of Decolonization". Archived from the original on March 23, 2006. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ^ Luci Yamamoto (2006). Kauaʻi. Lonely Planet. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-74059-096-9. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ "Kahoolawe 9". firstlandingmovie.com. Archived from the original on June 6, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Mooallem, Jon (May 8, 2013). "Who Would Kill a Monk Seal?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 6, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ Cicotello, Laurie (January 20, 2013). "Walter Ritte, Andrew Kimbrell address Hawaiʻi SEED event". The Garden Island. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ Sai, David Keanu. "Welcome – E Komo Mai". Hawaiian Kingdom Government. Honolulu, H.I. Archived from the original on November 25, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Tanigawa, Noe (August 29, 2014). "Hawaiʻi: Independent Nation or Fiftieth State?". hpr2.org. Honolulu, HI: Hawaii Public Radio. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- ^ "International Arbitration – Larsen vs. Hawaiian Kingdom". Waimanalo, HI: Aloha First. July 18, 2011. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ "Most provocative notion in Hawaiian affairs". Honolulu Weekly. Honolulu, HI. August 15–21, 2001. ISSN 1057-414X. OCLC 24032407. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ International Law Reports. Cambridge University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-521-66122-6. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- ^ Sai, David Keanu. "Dr. David Keanu Sai (Hawaiian flag raised with others)". Archived from the original on June 2, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "Permanent Court of Arbitration: About Us". Permanent Court of Arbitration. Archived from the original on March 29, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "Native Hawaiians seek to restore monarchy", Denver Post, AP, June 19, 2008, retrieved June 22, 2020

- ^ Park, Gene (May 1, 2008), "Group of Hawaiians occupies Iolani Palace, vows to return", Honolulu Star-Bulletin, retrieved June 22, 2020

- ^ Nakaso, Dan (May 15, 2008). "Native Hawaiian group: We're staying". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 25, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "Francis A. Boyle – Faculty". Champaign, IL: University of Illinois College of Law. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ "Kanuha Found Not Guilty Of Obstruction on Mauna Kea". Big Island Video News. Big Island video News. January 8, 2016. Archived from the original on January 10, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ "How Lanakila Mangauil came to Mauna Kea". The Hawaii Independent Corporation/Archipelago. The Hawaiian independent. Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation Archived January 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine "Originally named the 'Hawaiian Coalition of Native Claims,' the organization fought against a then-new wave of dispossession from the land to make way for a boom in urban development. Since then, NHLC has worked steadily to establish Native Hawaiian rights jurisprudence."

- ^ "Professor Noenoe Silva". Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. November 3, 2011. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ "Hawaii Suffering From Racial Prejudice". Southern Poverty Law Center. August 30, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ Webb, Michael; Webb-Gannon, Camellia (2016). "Musical Melanesianism: Imagining and Expressing Regional Identity and Solidarity in Popular Song and Video" (PDF). The Contemporary Pacific. 28 (1). University of Hawai'i Press: 59–95. doi:10.1353/cp.2016.0015. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 6, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Reconciliation at a Crossroads: The Implications of the Apology Resolution and Rice v. Cayetano for Federal and State Programs Benefiting Native Hawaiians". US Commission on Civil Rights. usccr.gov. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ Glenda Bendure; Ned Friary (2003). Oahu. Lonely Planet. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-74059-201-7. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ Jeff Campbell (September 15, 2010). Hawaii. Lonely Planet. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-74220-344-7. Archived from the original on May 17, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ Eva Bischoff; Elisabeth Engel (2013). Colonialism and Beyond: Race and Migration from a Postcolonial Perspective. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 61. ISBN 978-3-643-90261-0. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ Lyte, Brittany (September 16, 2015). "Native Hawaiian election set". The Garden island. The Garden Island. Retrieved October 6, 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Grass, Michael (August 12, 2014). "As Feds Hold Hearings, Native Hawaiians Press Sovereignty Claims". Government Executive. Government Executive. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ Office of the Secretary of the interior (June 18, 2014). "Interior Considers Procedures to Reestablish a Government-to-Government Relationship with the Native Hawaiian Community". US Department of the interior. US Government, Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ Hill, Malia Blom (January 2011). "Office of Hawaiian Affairs: Rant vs. Reason on Race". Honolulu, HI: Grassroot Institute of Hawaii. Archived from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- ^ "Supreme Court of the United States: Opinion of the Court". 2000. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Lauer, Nancy Cook (September 30, 2015). "Interior Department announces procedure for Native Hawaiian recognition". Oahu Publications. West Hawaii Today. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "Interior Proposes Path for Re-Establishing Government-to-Government Relationship with Native Hawaiian Community". Department of the Interior. Office of the Secretary of the Department of the interior. September 29, 2015. Archived from the original on October 26, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ Edward Hawkins Sisson (June 22, 2014). America the Great. Edward Sisson. p. 1490. GGKEY:0T5QX14Q22E. Archived from the original on May 18, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ Ariela Julie Gross (June 30, 2009). What Blood Won't Tell: A History of Race on Trial in America. Harvard University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-674-03797-7. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ a b Rick, Daysog (October 6, 2015). "Critics: Hawaiian constitutional convention election process is flawed". Hawaii News Now. Hawaii News Now. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ "Fed Appeals Court Won't Stop Hawaiian Election Vote Count". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 19, 2015. Archived from the original on December 1, 2015. Retrieved November 28, 2015.

- ^ "Opponents Ask High Court to Block Native Hawaiian Vote Count". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 24, 2015. Archived from the original on December 1, 2015. Retrieved November 28, 2015.

- ^ "Supreme Court Justice Intervenes in Native Hawaiian Election". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 27, 2015. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Andrade Jr., Ernest (1996). Unconquerable Rebel: Robert W. Wilcox and Hawaiian Politics, 1880–1903. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0-87081-417-6

- Budnick, Rich (1992). Stolen Kingdom: An American Conspiracy. Honolulu: Aloha Press. ISBN 0-944081-02-9

- Churchill, Ward. Venne, Sharon H. (2004). Islands in Captivity: The International Tribunal on the Rights of Indigenous Hawaiians. Hawaiian language editor Lilikala Kameʻeleihiwa. Boston: South End Press. ISBN 0-89608-738-7

- Coffman, Tom (2003). Nation Within: The Story of America's Annexation of the Nation of Hawaii. Epicenter. ISBN 1-892122-00-6

- Coffman, Tom (2003). The Island Edge of America: A Political History of Hawaiʻi. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2625-6 / ISBN 0-8248-2662-0

- Conklin, Kenneth R. Hawaiian Apartheid: Racial Separatism and Ethnic Nationalism in the Aloha State. ISBN 1-59824-461-2

- Daws, Gavan (1968). Shoal of Time: A History of the Hawaiian Islands. Macmillan, New York, 1968. Paperback edition, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1974.

- Dougherty, Michael (2000). To Steal a Kingdom. Island Style Press. ISBN 0-9633484-0-X

- Dudley, Michael K., and Agard, Keoni Kealoha (1993 reprint). A Call for Hawaiian Sovereignty. Nā Kāne O Ka Malo Press. ISBN 1-878751-09-3

- J. Kēhaulani Kauanui. 2018. Paradoxes of Hawaiian Sovereignty: Land, Sex, and the Colonial Politics of State Nationalism. Duke University Press.

- Kameʻeleihiwa, Lilikala (1992). Native Land and Foreign Desires. Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 0-930897-59-5

- Liliʻuokalani (1991 reprint). Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen. Mutual Publishing. ISBN 0-935180-85-0

- Osorio, Jonathan Kay Kamakawiwoʻole (2002). Dismembering Lahui: A History of the Hawaiian Nation to 1887. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2549-7

- Silva, Noenoe K. (2004). Aloha Betrayed: Native Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3349-X

- Twigg-Smith, Thurston (2000). Hawaiian Sovereignty: Do the Facts Matter?. Goodale Publishing. ISBN 0-9662945-1-3

External links

[edit]- Native Hawaiians Study Commission (December 7, 2006). "Native Hawaiians Study Commission Report – GrassrootWiki". Honolulu, HI: Grassroot Institute of Hawaii. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- morganreport.org Online images and transcriptions of the entire Morgan Report

- Historic Hawaiian-language newspapers Ulukau: Hawaiian Electronic Library: Hoʻolaupaʻi – Hawaiian Nupepa Collection

- Hui Aloha Aina Anti-Annexation Petitions, 1897–1898

Politics

[edit]- "Hawaiian Journal of Law and Politics". Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii at Manoa. ISSN 1550-6177. OCLC 55488821. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- "Hawaiian Society of Law and Politics". Archived from the original on August 19, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- Office of Hawaiian Affairs

- Ka Lahui Archived October 5, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Nation of Hawaiʻi

Media

[edit]- Michael Tsai (August 9, 2009). "Pride in Hawaiian Culture Reawakened: Seeds of Sovereignty Movement Sown during 1960s–70s Renaissance". Honolulu Advertiser. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011.

- Native Hawaiians battle in the courts and in Congress Archived February 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Honolulu Advertiser chronology of legislative and legal events relating to Hawaiian sovereignty since 1996

- Political tsunami hits Hawaii, by Rubellite Kawena Kinney Johnson

- Blog of articles and documents on Hawaiian sovereignty

- Indigenous students silent no more Archived November 25, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, article from Honolulu Star-Bulletin on Native Hawaiian student activism at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

- Sovereign Stories: 100 Years of Subjugation Archived March 11, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, article from Honolulu Weekly

- Resolution on Kānaka Maoli Self-Determination and Reinscription of Ka Pae ʻĀina (Hawaiʻi) on the U.N. list of Non-Self-Governing Territories, In Motion Magazine

- Connection between Hawaiian health and sovereignty Archived May 16, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, paper by Dr. Kekuni Blaisdell presented August 24, 1991, at a panel on Puʻuhonua in Hawaiian Culture

- Nā Maka O Ka ʻĀina: award-winning documentary, film/video resources, and sovereignty-related A/V tools

- 2004 Presentation given by Umi Perkins at a Kamehameha Schools research conference Archived January 10, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- Noho Hewa: Documentary by Anne Keala Kelly

Opposition

[edit]- Documents and essays opposing sovereignty collected or written by Kenneth R. Conklin, Ph.D.

- Grassroot Institute of Hawaii – co-founded by Richard O. Rowland and Hawaii Reporter publisher Malia Zimmerman

- Aloha for All – co-founded by H. William Burgess and Thurston Twigg-Smith

- "Hawaii Reporter: Hawaii Reporter". March 21, 2003. Archived from the original on May 22, 2006.